Key concepts

Sex

Sex- Gender Identity

- Gender Role

- Sexual Orientation

- Intentions

- Values

(Althof, 2000; Yarhouse, 2001; Lev, 2004)

Sex

It refers to femininity or masculinity of a person, determined by biological factors:

- sex chromosomes (chromosomal sex )

- presence of male or female gonads (gonadal sex)

- hormones (endocrine sex)

- internal sex organs, external sexual organs and secondary sexualcharacteristics (phenotypic sex)

- sexual differentiation of the brain

(WHO, 2002; Simonelli, 2007)

Gender Identity

Gender identity refers to a person’s basic sense of self as male, female or ambivalent. It includes both the awareness that one is male or female and an affective appraisal of such knowledge.

(Money, Ehrhardt, 1972; Zucker, Bradley, 2005)

Gender Role

All those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman or ambiguous, respectively. It includes, but is not restricted to sexuality in the sense of eroticism. It is the public expression of gender identity.

(Money, Hampson, and Hampson 1955; Money, Ehrhardt, 1972)

Sexual Orientation

It refers to the tendency of the person to respond with

sexual arousal to certain stimuli rather than others. - Towards persons of the opposite sex -> Heterosexuality

- Towards persons of the same sex -> Homosexuality

- Towards both sexes -> Bisexuality

Recently, some authors have proposed the concept of

“sexual fluidity” or “erotic plasticity”.

(Baumeister, 2000; Diamond, 2008)

Intentions and Values

Intention and valuational framework: what one intends to do with the desires one has in light of one’s beliefs and values.

(Althof, 2000; Yarhouse, 2001)

– For example, a person with strong homosexual tendencies may decide, following his/her intentions or values, not to engage in homosexual behavior, giving in fact a less central role to sexual identity and a more relevant one to other aspects of identity

Sexual Development and Interpersonal Relationships

- Freud’s theory of infantile sexuality (1905)

- Bowlby’s attachment theory (1958)

- Infant Research (Stern, 1985)From the importance of the father figure in the classical Freudian model, we moved to the prominent role of the mother figure: initially the child was thought of as essentially passive and/or undifferentiated from the mother, then the child was seen as checking a sort of “competence”, innate firstly and learned later on, in interpersonal relationships. In essence, every human being seems to be modelled by an innate program that is in constant interaction with the “program” of his/her parents, environment and culture.

Zeuthen, Gammelgaard, 2010

Fetal period

- The fetus manifest expressions of pleasure at the 15th week, both sucking the finger and swallowing sweet substances that can be injected into the amniotic fluid.

- The male fetus presents erections within a few months before birth; similarly, in single day newborn females vaginal lubrication and clitoral swelling can be noticed.

- Research conducted on children still in the uterus and then for one year after birth has shown how much correspondence there is between intra-uterine and extra- uterine behavior.

Masters, Johnson, 1986; Giorni, Siccardi, 1996; Johnson, Maxwell, 2000

First months of life

- Implicit memory

- Parent-child contact during physical care and play

- Parents’ reactions to the child’s sexual reflexes

- Self-stimulation of the genitals:

- Males: appears at 6-7 months, becomes recurrent around 15-16 months

- Females: appears at 10 months, remains intermittent and

occasional, with preference for indirect methods

Galenson, Roiphe, 1974

3-5 years:

gender and role identity

- There are no sex-specific preferences in the choice of leisure activities, thus showing a lack of sex role differentiation even in the presence of a well-defined gender identity.

- Males, thanks to the “matriarchal” context, at this age stillperform pleasure activities such as sewing, cooking and ironing.

- Verbal and physical aggressive behavior is present more in boys than in girls, and the same goes for high-risk behavior.

- Girls show empathy and seek reparation contact more often than males do.

Simonelli, 2007

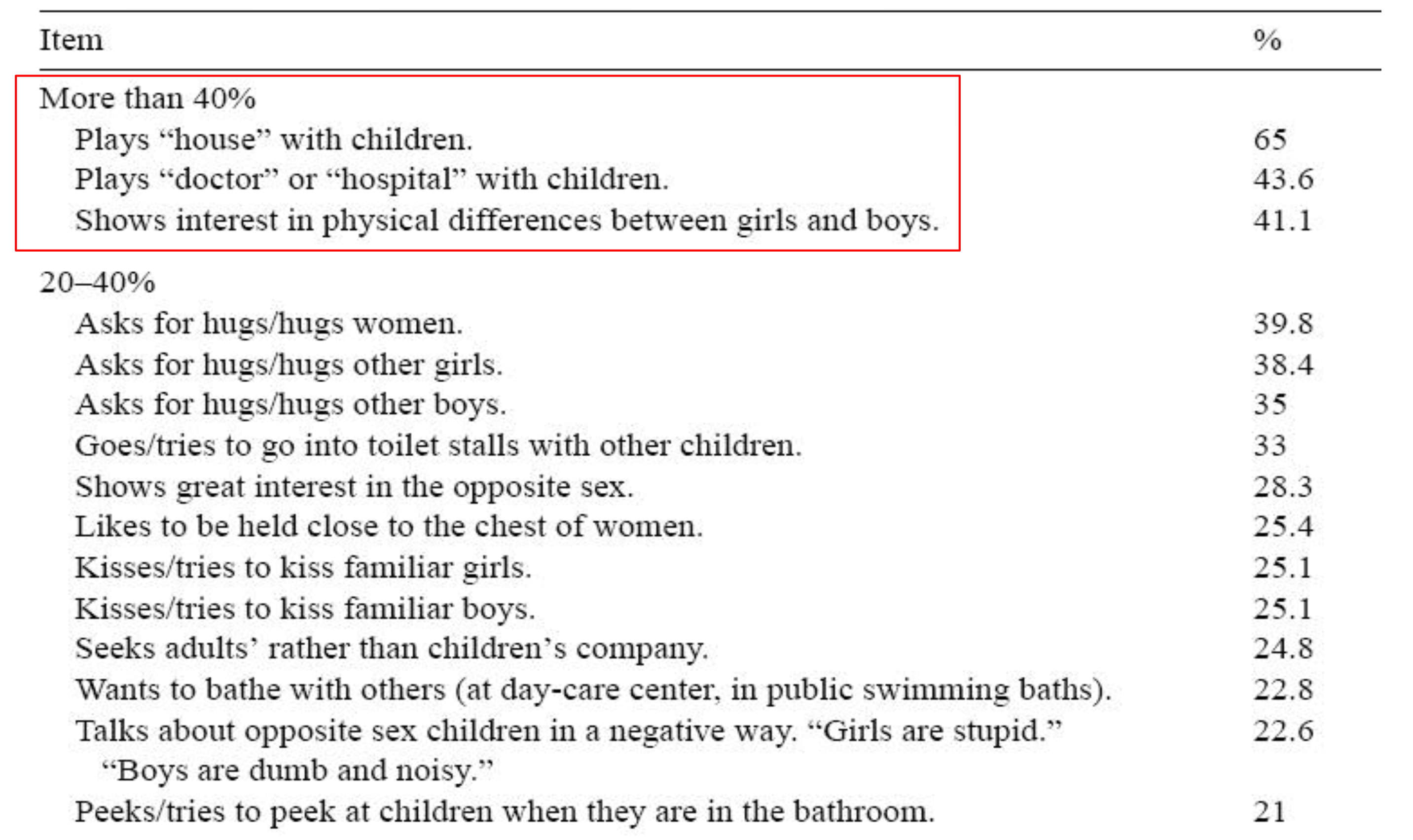

2-7 years: behavior

The most  frequently reported child sexual behaviors were characterized by bodily contact, toilet behavior, sexual interest, self-exploration, genital play and interest, sexual behavior together with other children, sexual verbalization, and voyeuristic behavior. These characteristics

frequently reported child sexual behaviors were characterized by bodily contact, toilet behavior, sexual interest, self-exploration, genital play and interest, sexual behavior together with other children, sexual verbalization, and voyeuristic behavior. These characteristics

are referred to as “natural and

healthy sexual play”.

Behaviors varied according to age.

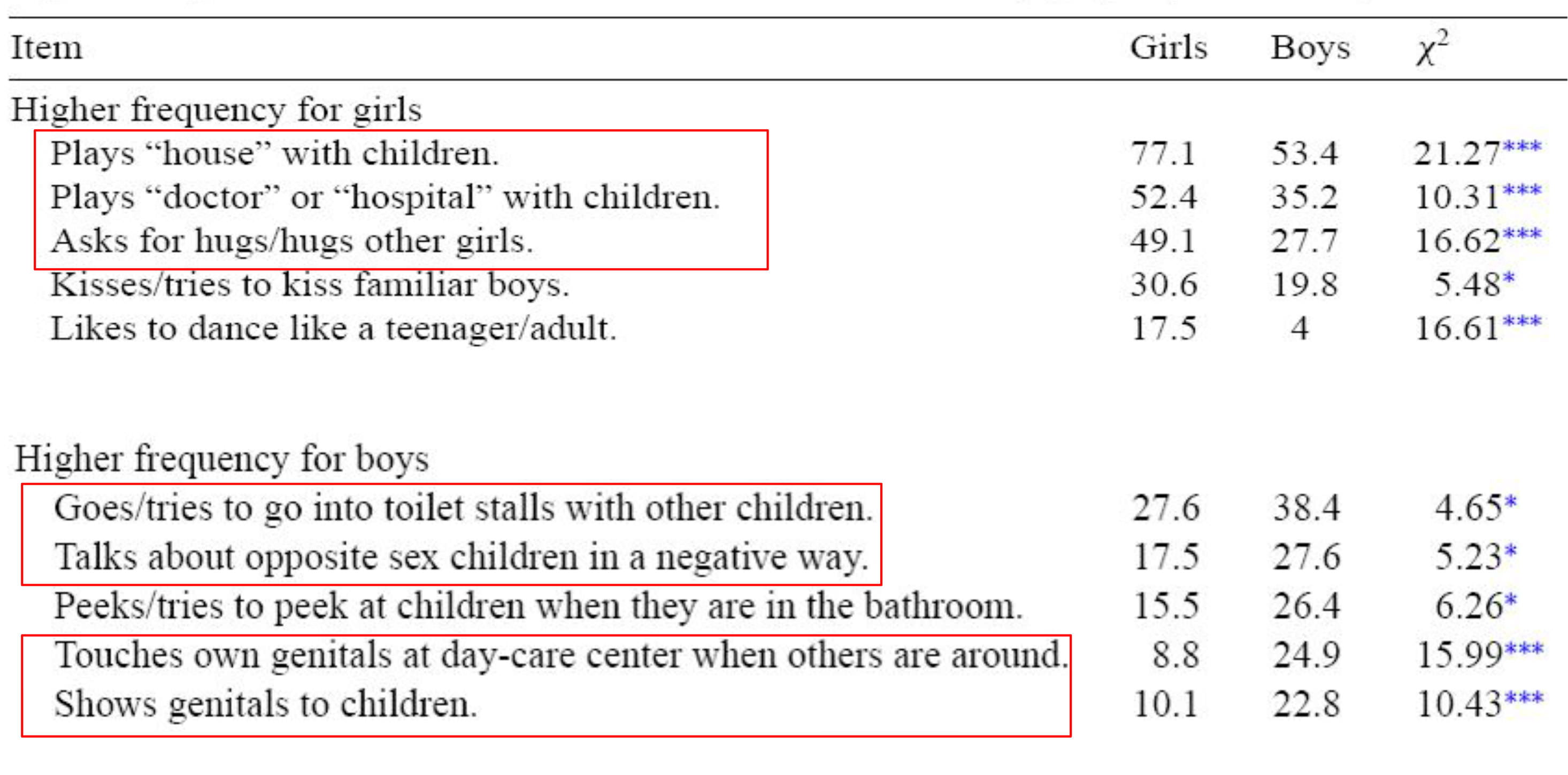

2-7 years: gender differences

- Girls had a higher frequency of domestic and gender role exploring behaviors (with a more social character, like expression of endearment towards others, as well as appearances of flirtation), whereas the boys tended to engage in explorative acting and information-seeking behaviors (exhibitionistic touching of self, sexual verbalization, a general interest in nudity).

- No gender differences for:

- talking negatively about children of the opposite sex and games with sexual and romantic elements (increase with age)

- behaviors related to development and expressed interest in the characteristics of opposite gender (decrease with age)

Table 1

Frequencies of reported sexual behaviors of 2- to 7-year-old boys and girls

![]()

Table 3

Significant gender differences in the observed sexual behaviors (age groups combined)

![]()

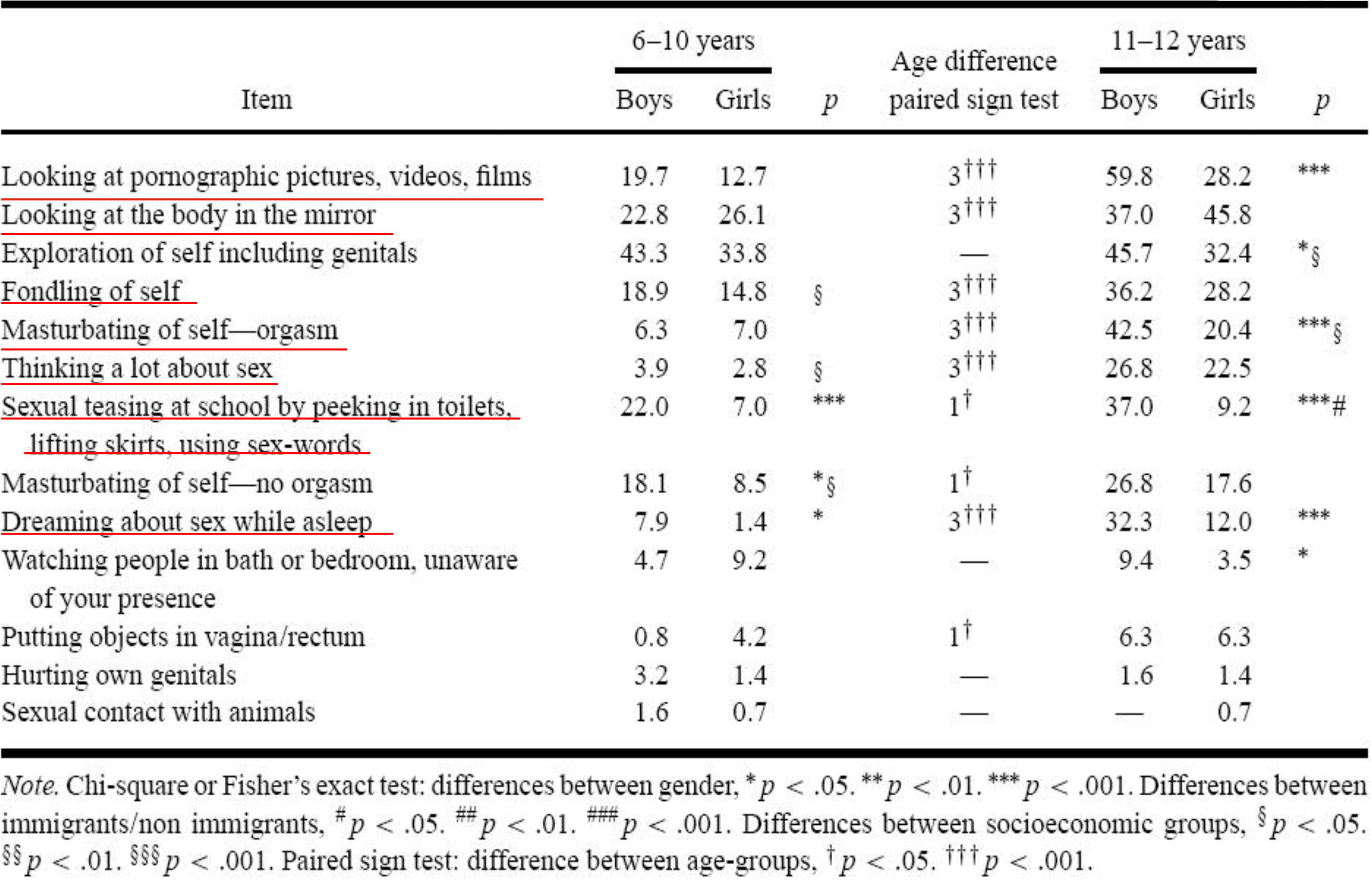

6-12 years: behavior

The years before puberty seem to be years of frequent sexual exploration and experimentation, rathen than “sleeping sexuality” or latency.

The years before puberty seem to be years of frequent sexual exploration and experimentation, rathen than “sleeping sexuality” or latency.- More than 80% of the children had had solitary experiences and/or mutual sexual experiences together with another child.

- Sexual experiences exploring their own body increase prior to puberty, whereas looking at and exploring genitals together with peers decrease after 10 years of age.

6-12 years: gender differences

- Boys seem to be more active than girls in exploring their own body as well as in exploration together with another child.

- Although girls experienced a wide range of consensual activities,they were also more often drawn into non-consensual activities.

- Solitary masturbation was almost twice as common among boys (62%) than among girls (36%) before the age of 13.

- Boys reported a more positive attitude to their own experiences, whereas girls often reported feelings of guilt.

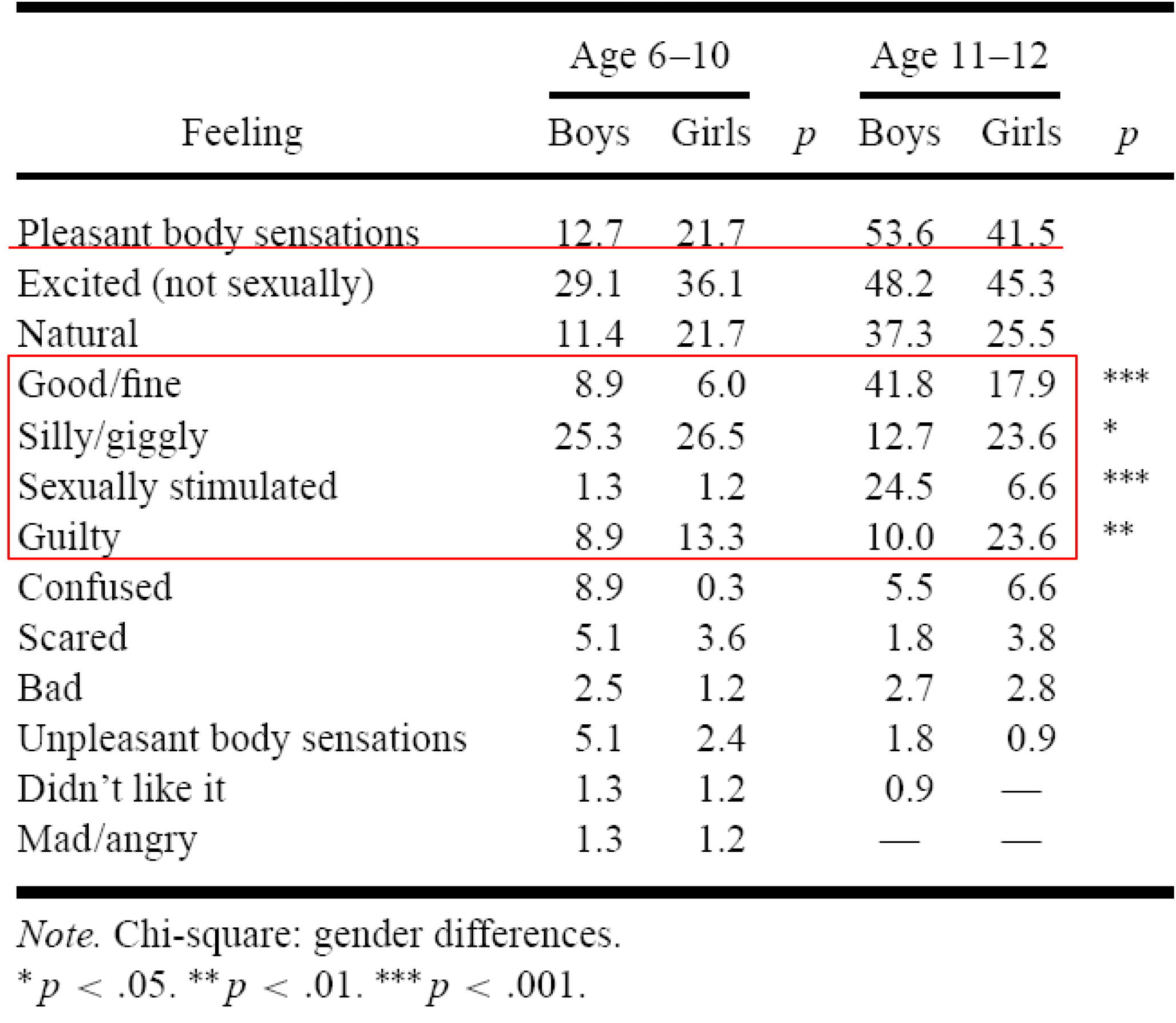

Table II. Solitary Sexual Activities in Different Ages (%)

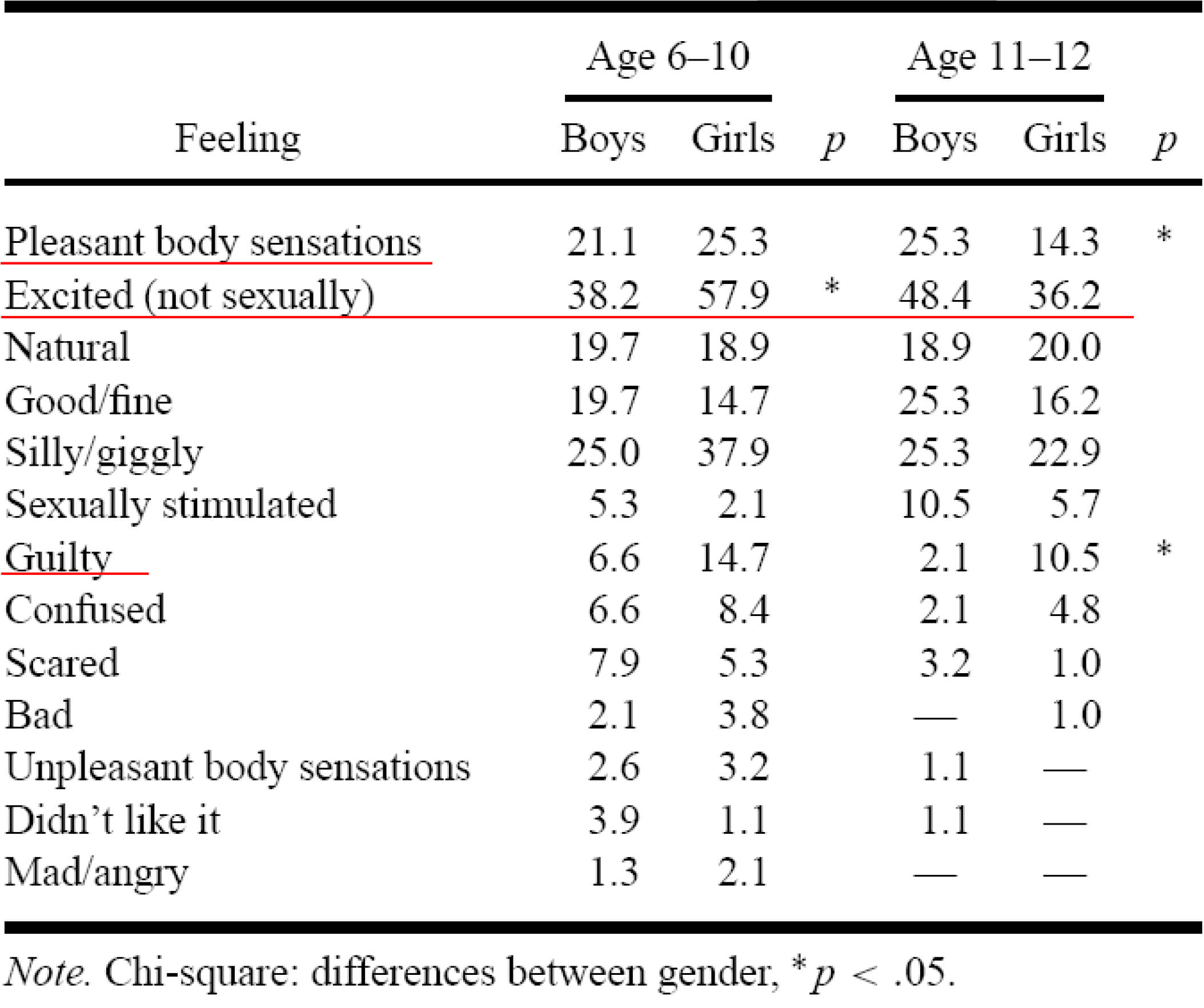

Table III. Feelings About Solita1y Sexual Activities (%)

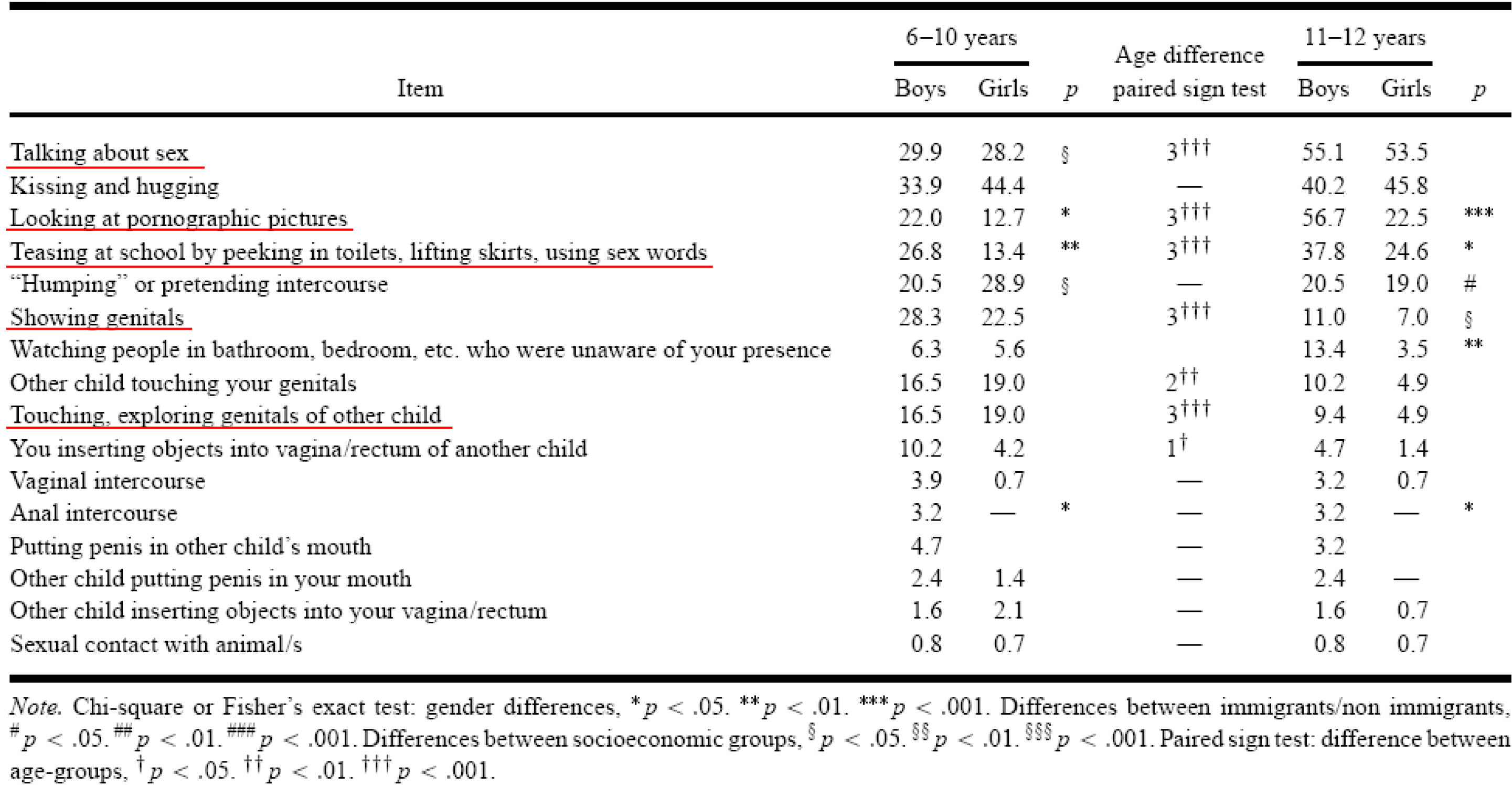

Table IV. Mutuai Sexual Experie11c.es Together With A11other Child (%)

Table V. Feelings About Mutua!Sexual Experiences (%)

REVIEW

Practical approach to childhood masturbation – a review

Charita Mallants – Kristina Casteels

Received: 23 February 2008 / Accepted: 14 May 2008 / Published online: 25 June 2008

Ⓒ Springer- Verlag 2008

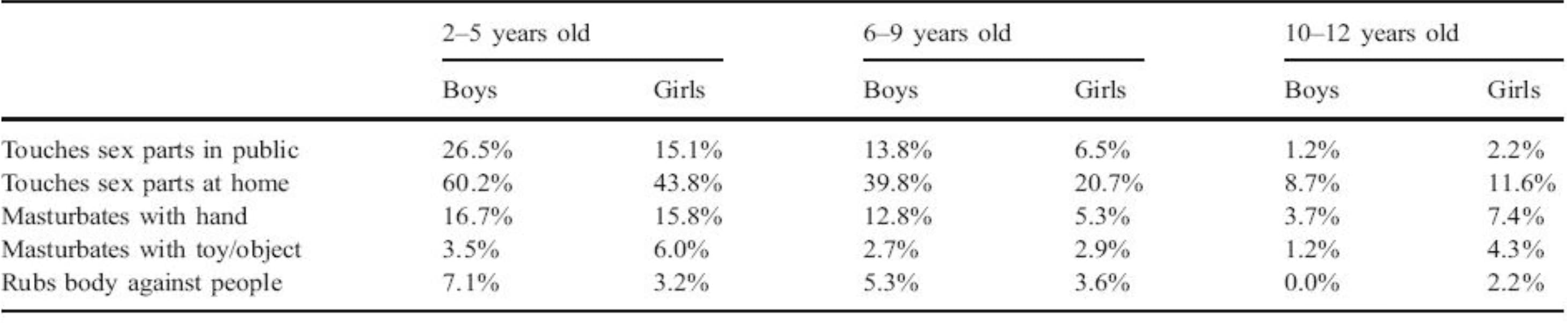

Table 1 Frequencies of some sexual behaviours for the three age groups in boys and girls [1O]

CM: common features

- Episodes of stereotyped posturing of the lower extremities and/ormechanical pressure on the perineum or suprapubic area

- Associated intermittent (quiet) grunting, irregular breathing, facial flushing and diaphoresis

- Variable duration of the episode (lasting from a few seconds to several hours) and variable frequencies of episodes (ranging from once in a while to almost continuously)

- No alteration of consciousness

- Cessation with distraction

- The episodes cannot be explained by abnormalities on physical examinations

Yang et al., 2005; Mallants et al., 2008

Clinical features

A lack of awareness by the clinical practioner could result in anxiety for the parents and unnecessary investigations for the child.

When there is no evidence of other problems, the clinical practitioner can focus on parental education and guidance.

This helps the parents change from viewing their child’s behaviour as evidence of disease to considering it as a harmless, non-painful habit.

Mallants et al., 2008

Managment of CM

Attempts to stop the behaviour immediately are likely to be frustrating and prohibition or punishment of the behaviour tends to reinforce it.

It is better to ignore this behaviour or to distract the child during his or her masturbatory activity.

When possible, the child should also receive sex information, appropriate for their age. In this way, he/she will learn what is socially accepted and what is not. Although (overt) childhood masturbation often ceases eventually spontaneously, further follow-up is advised.

Unal, 2000

Key messages

1. SD depends on the physiological regulation, as well as on interaction with significant others.

2. Masculinity and femininity, both as traits and as social constructs, are offered in primary relationships, and internalized by the child in versions more or less flexible and articulated.

3. Mental disorders, especially during the developmental age, cannot be understood solely as the result of intra- psychic conflict, but as a symptomatic expression of disturbed relational patterns that appear and are internalized at an early stage.